There are countless theories and classifications of art. But the one I found the most useful I learned from Robin Hanson.

Here's how it works:

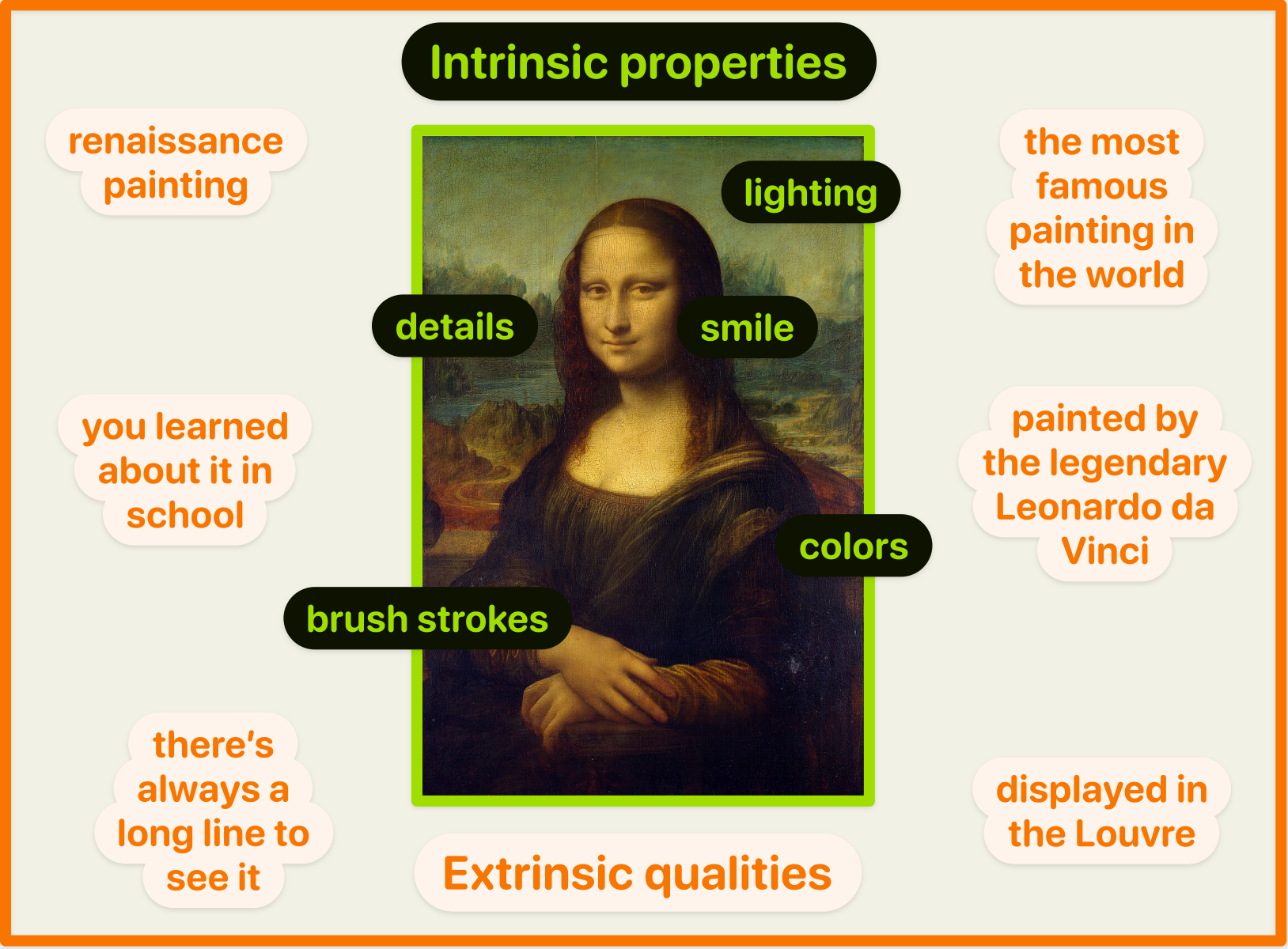

“Intrinsic properties are the qualities that reside “in” the artwork itself, those that a consumer can directly perceive when experiencing a work of art. We might also think of them as perceptual properties.

The intrinsic or perceptual properties of a painting, for example, include everything visible on the canvas: the colors, textures, brush strokes, and so forth.

Extrinsic properties, in contrast, are factors that reside outside of the artwork, those that the consumer can’t perceive directly from the art itself.

These properties include who the artist is, which techniques were used, how many hours it took, how “original” it is, how expensive the materials were, and so on.”

In other words, intrinsic properties are elements of art that everyone can perceive, even uneducated audiences like tribes seeing our culture for the first time.

Extrinsic properties are closer to an "acquired taste," where you need to learn about an artist, their domain, or the art itself to appreciate it fully.

So when someone says that a banana taped to a wall is not art, what they are really saying is: "I care about intrinsic properties of an art more than extrinsic" or "I don't buy the narrative behind this art."

And my theory is that the focus on extrinsic properties is what makes so many people hate contemporary art.

Why do people hate contemporary art

The way many people think about contemporary art is more or less like this:

It’s ugly and overintellectualized. You can produce something that doesn’t make sense and then add a narrative afterward to scam rich people who are scared to say that the Emperor has no clothes. And they play along because they are into art for status - they want to be in this small club of sophisticated “socialites” who “get it” while peasants don’t.

And if you look at projects like Balenciaga mud runway, it's hard to ignore this point of view.

Even if we set aside the idea that a big part of contemporary art is a group hallucination of bored, pretentious people, you need to spend a lot of time educating yourself to really experience the art. This means art is becoming less available to the average person and less democratized.

An average person can go to the Louvre, know zero about art, and appreciate almost everything they see there because the intrinsic qualities of the art pieces are fantastic. It's harder to experience that in the contemporary art museum (though there are many pieces there that are intrinsically and extrinsically stunning!).

And even if someone tries to learn more about art, some of these stories might sound silly:

Cattelan has been working on the idea for Comedian for about a year, first creating versions in bronze and resin. Somehow, they were lacking. “Wherever I was traveling I had this banana on the wall. I couldn’t figure out how to finish it,” Cattelan told me when Perrotin handed me the phone with him on the line. “In the end, one day I woke up and I said ‘the banana is supposed to be a banana.'”

The artist wouldn’t speak to the work’s meaning, but he was partially inspired by the large number of paintings he’s seen at galleries recently. “I’m not in Miami, but I’m sure it’s full of paintings as well,” said Cattelan. “I thought maybe a banana could be a good contribution!”.

And if many people focus on art to display their sophistication, then how do you know if a guy who taped a banana to a wall hadn't just gotten drunk, did that spontaneously, and added the narrative afterward? If that's the truth, then you are not sophisticated - you're a person who has fallen for a con man.

And I think this is what makes many people uneasy about big parts of today's contemporary art. Its value is so subjective and dependent on the narrative that they don't know what is true (which is btw an interesting meta-commentary to today's world).

But… all of us care about the story behind the art and artists, at least a little bit.

We all fall for art narratives

Most of us would rather see the original Mona Lisa than a replica.

But why? It shouldn't matter if we only cared about the visual, intrinsic qualities. Apparently, we care about extrinsic qualities - being able to see the most famous painting in the world, feel the mystical presence of da Vinci's masterpiece, and so on.

This is funny since - as you probably know - for most of its history, the Mona Lisa wasn't a popular piece of art. It became widely popular only after it was stolen in 1911. Extrinsic properties strike again.

Also, the fact that you can see it in the Louvre is an extrinsic property - we all know that the Louvre has the best art pieces in the world. If the Mona Lisa were hung on a wall of some small village's museum, it'd get less attention.

And the "Mona Lisa" narrative is extremely powerful.

I'm an intrinsic first-person and don't like over-narrated art - I'm in a "Show, don't tell" camp. But still, I'd rather watch the ashes of the Mona Lisa than the indistinguishable replica.

And, per Robin Hanson's book, I'm no different than 80% of people:

“When researchers Jesse Prinz and Angelika Seidel asked subjects to consider a hypothetical scenario in which the Mona Lisa burned to a crisp, 80 percent of them said they’d prefer to see the ashes of the original rather than an indistinguishable replica. This should give us pause.”

Although that sounds strange, it's not that strange when you think about the last 200 years of progress.

Commoditization of intrinsic properties

Paintings and sculptures, for example, were prized for their realism, that is, how accurately they depicted their subject matter. Realism did two things for the viewer: it provided a rare and enjoyable sensory experience (intrinsic properties), and it demonstrated the artist’s virtuosity (extrinsic properties).

There was no conflict between these two agendas. This was true across a variety of art forms and (especially) crafts. Symmetry, smooth lines and surfaces, the perfect repetition of geometrical forms—these were the marks of a skilled artisan, and they were valued as such.

Then, starting in the mid-18th century, the Industrial Revolution ushered in a new suite of manufacturing techniques. Objects that had previously been made only by hand—a process intensive in both labor and skill—could now be made with the help of machines. This gave artists and artisans unprecedented control over the manufacturing process.

Walter Benjamin, a German cultural critic writing in the 1920s and 1930s, called this the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, and it led to an upheaval in aesthetic sensibilities.

No longer was intrinsic perfection prized for its own sake. A vase, for example, could now be made smoother and more symmetric than ever before—but that very perfection became the mark of cheap, mass-produced goods. In response, those consumers who could afford handmade goods learned to prefer them, not only in spite of, but because of their imperfections.“

So per this passage, our "handmade taste" is largely acquired. In the overabundance of intrinsically aesthetic things, the extrinsic properties become more important.

So, we like things that are rare, unique, and made by other humans. Whether it's "tailor-made" fashion vs. "pret-a-porter" clothing or buying a handmade vase on a flea market vs. getting one made in China.

The same story has happened with paintings:

The advent of photography wreaked similar havoc on the realist aesthetic in painting. Painters could no longer hope to impress viewers by depicting scenes as accurately as possible, as they had strived to do for millennia.

“In response,” writes Miller, “painters invented new genres based on new, non-representational aesthetics: impressionism, cubism, expressionism, surrealism, abstraction. Signs of handmade authenticity became more important than representational skill. The brush-stroke became an end in itself.”

It has become more about the art and the process than the painting itself. A great example is Picasso's "Bull," where he shows how a picture of a bull evolves into a famous Picasso signature:

The best art, though, highlights both qualities. Pieces by Picasso and Salvador Dali are both intrinsically and extrinsically amazing. And so are Refik Anadol’s.

Today, after years of exploration, we tipped the scales to extrinsic-first art. I believe that AI models such as Midjourney & DALL-E, where it's extremely easy to create something that looks good, are going to point us in that direction even more.

So what's going to change?

How blockchains can save contemporary art

Blockchains have already done a lot for artists.

They let them sell their pieces directly to collectors, skipping the gallery middlemen. They give them access to global (crypto) markets instead of local ones. And everyone can check the provenance of the art without spending $50,000 on an art expert.

But that's not all. The free NFT markets added another layer of extrinsic qualities.

The fact that some NFT art piece becomes popular on Twitter is an extrinsic quality. And when everyone is talking about the piece, its memetic value rises and makes us more interested in it. There are already masters of this free art market; one of them is Jack Butcher, who explains his approach in a ZORA interview.

The thing you couldn't do before outside the auctions is measure the art's popularity by its price proposed by other collectors. Now you can easily do it by checking the NFT floor price & volume on OpenSea. It gives us another way of checking what other people are thinking about this piece of art and how much they value it. So experiencing and valuing art becomes a more mimetic & social experience than ever.

But what if AI becomes better in art than the best humans? It's a hard question to answer, but we can look at a sphere where AI has been better for at least a quarter of a century. Yes, we'll talk about chess.

AI can beat humans in chess since Deep Blue won with Kasparov in 1997. To give you perspective - it's the same year Diablo & Fallout got released, which means it was at least a few computational eras ago.

Yet chess fans still love chess. And they are much more interested in Magnus Carlsen games than chess tournaments between AI models. If they only cared for the quality of the game (intrinsic quality), they should watch AI, which could beat Magnus every time, right?

But they don't. Because we are interested in what humans are capable of (extrinsic quality), not what's possible for some robots.

That's why, since "Queen's Gambit" added a fresh extrinsic narrative layer over an old game, the chess popularity went up. It was all about the story.

Same with arts. We are interested in what humans can create with their minds and hearts, not robots. And there's already some research suggesting that people dislike the art when they learn it's been AI-generated.

So, if art is about an artist, what can an artist do?

I believe there's going to be a strong draw to focus on physical (check Refik Anadol's Unsupervised in MoMA), handmade things (paintings & sculptures are back?), live performances, recording the artistic process and highlighting the human touch.

And although the average Joe thinks of AI art as "sending prompts to Midjourney", I'd say that it's closer to photography.

It's extremely hard to paint a realistic painting, but it doesn't take any skill to take a realistic photo. Yet, taking a good studio photo is a complicated process.

Most of the work is focused on planning the session, choosing the right lights, picking the background, testing the cadres, and so on. Then you take 1,000 pictures, pick the best 5, and polish them in Lightroom and Photoshop.

So, although the tool (camera) makes it easy to take good pictures, there are many more layers of expertise on top of clicking the "Take a photo" button.

Both used the camera, but we can easily notice the artistry in Leibovitz's take.

And I believe the same is going to happen with AI. The tool (Midjourney & DALL-E) makes it easy to create "another generic Midjourney-looking art." But it's harder to create something truly remarkable.

I believe more and more artists are going to explore this way. Choose the right prompts or pictures they want to use to inspire AI. Test different versions. Create 1,000 of them, pick the best ones, and manually modify them to get the best result.

The great thing about blockchain, though, is that artist can record each step of their artistic process. And just like Picasso's Bull, show where you come from, how their ideas got connected, evolved, and transformed into a single piece a person is holding.

I believe it's a huge deal because - in a world flooded with intrinsically good-looking art - it lets artists highlight the extrinsic qualities of the thing they worked on. By minting NFTs for each step, they can create this "Proof of Process" that strengthens the narrative.

And no one will think that an artist taped the banana to the wall because they got drunk. There's no risk that you're going to fall for a con man. Artists can even put each step in an ERC-6551 NFT, where the resulting piece holds all the steps that led to it.

This, in turn, would make the extrinsic part of work easier to consume and understand. Each step and accompanying narrative would become a part of the art itself, which means you won't need to study art magazines to get excited about the art.

That would make art more accessible to common people and more democratized, which would result in more demand for their work and more independence from tastemakers who are saying, "What's hot and what's not".

And this is something I hope we all achieve.